By Oliver Houghton & Rigardt Jonker

At Andile, our stated aim is to “Make markets thrive”. This mission also applies to the work that we deliver to Risk functions across different industries. This article is the first of a series in which we explore different themes and problems in the risk space, with the aim of coming up with viable solutions to problems that Risk has experienced.

It is worth noting that if you put 10 risk professionals in a room, chances are that you will get 12 different opinions. We do acknowledge that not every risk professional will agree with some of the stated positions that Andile Risk has taken, and that is fine because we want to stir debate in the Risk community. The more debate we have on these topics, the more energy can be poured into solutions for problems that vexes the industry. Another thing to keep in mind is that in the world of Risk, it is very seldom that we will come up with perfect solutions, part of the problem (and fun) in an industry which is part science, part art and where subjectivity often rules the day! Frequently decisions need to be based on options that have numerous pro’s and cons and the winner will normally be the option with the least or best understood drawbacks. To a large extent, we will focus on Risk through an Enterprise Risk Management and Operational Risk lens, but it is worth noting that Andile does consult on all risk types.

From an Andile perspective, the feeling is that business has not been given a proper seat at the table when it comes to solving for risk management. In the pursuit of generating profit, a business has to take risk. Risk exists because of business activity, not vice versa, therefore you cannot divorce the two concepts from each other. The fact that business needs are not properly solved for by Risk is a major cause in the siloed approach we see when it comes to managing business and risk.

To kick of our series on Risk, we will first look at the evolution of Operational Risk.

Operational Risk

Formal requirements for managing Operational Risk have only been in effect since 2004, when Basel II was introduced. At the time Operational Risk was referred to as “everything other than credit and market risk”. Given that context, the discipline is young.

It is interesting, in that since the publication of Basel II, the Operational Risk methods and practices that organisations are using have not evolved much, despite the radical evolution of operational risks that businesses face. This lack of evolution is peculiar, as arguably Operational Risk Management has not really added the value that businesses have been expecting – a perspective that is commonly observed and corroborated by continuing losses, fines, and unpleasant surprises.

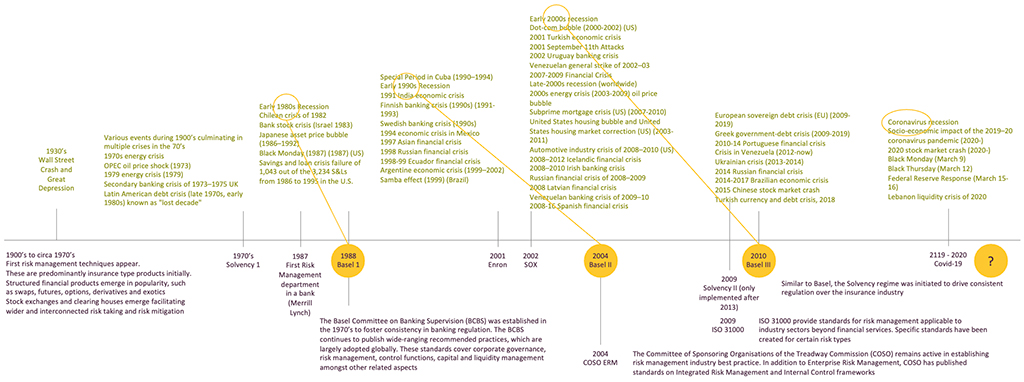

A brief reflection on the history of Risk Management may provide some insight into why risk disciplines are where they are today, this is particularly true for Operational Risk. The sequence of events that give rise to new risk management requirements generally follows a similar pattern: something happens (e.g. a crisis), new regulations are promulgated after a passage of time and then industry implements them. Typically, this is what happens, and it is a protracted and lengthy process.

An observable sequence of reactive responses

A case in point is BCBS 239, Principles for effective Risk Data Aggregation and Risk Reporting. Published in January 2013, post the Global Financial Crisis of 2007-2009 (GFC); in 2025 many organisations were still grappling with its implementation.

This reflection on the past reveals a few things:

- Regulations drive the risk management response.

- Regulations come too late.

- Risk managers are either not proactive, or do not have the tools to appropriately manage the risks; and

- The rapid pace of technology evolution leads to the creation of new services and products by businesses, and the Risk function can simply not keep up with this rate of change.

Regulations and industry practices have shaped what is implemented across financial services organisations globally. When a new requirement lands at the door, there is a demonstrable and urgent implementation effort, with milestones and success criteria measured in terms of the regulatory text. It normally follows the following pattern: gap analysis, impact assessment, project plan, deadline and execute.

The net effect is generally costly, strung-out implementation efforts which tick the regulatory ask, but have not answered the risk management need – “what difference has this made to the organisation’s ability to manage risk more effectively?” This plays out for almost every regulation, regardless of its source, and the inevitable outcome is the rise of governance and control. This is something that should be relatable to many in the risk fraternity.

Few would argue that risk management is not proactive enough. This is demonstrated by observable and recurring crises, the fact that regulation typically drives the risk management response, and the general implementation approach adopted for new regulations, which seeks to address compliance and evidence associated governance and control.

This in turn raises flags for the understanding of Operational Risk. If Operational Risk were properly understood, risk management responses would be more robust and more proactive, as opposed to demonstrating the existence of controls.

Or should the blame focus on the tools that are used to manage Operational Risk?

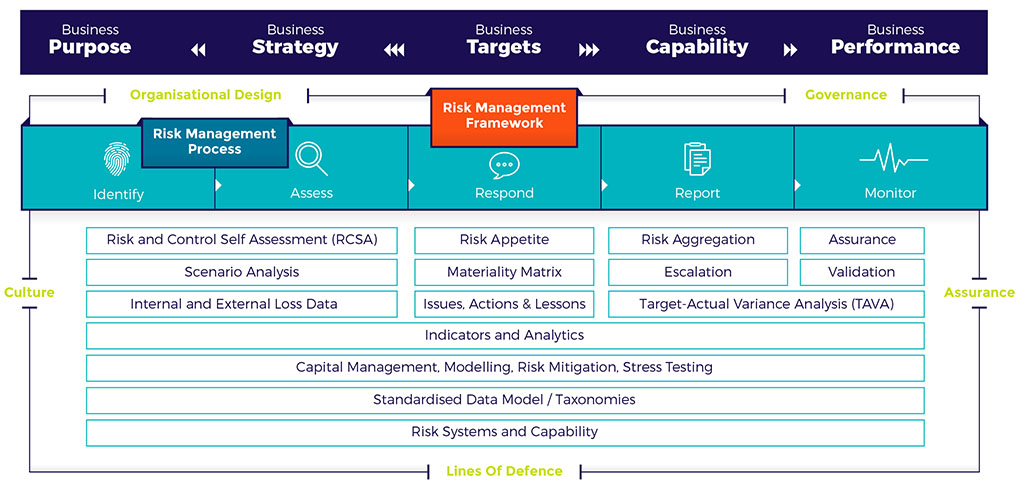

The risk management methods of a typical Operational Risk Management Framework (ORMF) have not changed materially since their inception. These tools are designed to enable the identification and assessment of actual and potential operational risks, and the consequent implementation of appropriate responses. An example of what an ORMF might look like is shown here.

The theory behind Operational Risk Management and its methods is sound; however, it is how these methods are implemented that can be the difference between understanding risk exposure and missing it completely.

Problems with how operational risk methods are implemented

- The Risk and Control Self-Assessment (RCSA) is oriented towards a “control” response. To control a risk exposure is one option of many, and the RCSA pre-ordains a one-dimensional response, which could be counter-productive to the strategy of the organisation and reinforces the artificial governance and control agenda.

- Many organisations also assess predefined risks and controls only, narrowly focusing on a library of risks and ignoring the reality and the horizon.

- Another common problem is to ignore the business context – when this happens, a true understanding of operational risks is not possible.

- Operational Risk Appetite and Materiality Matrices (risk assessment matrices) have not enabled organisations to understand the true extent or implications of risk exposures, due to inherent flaws in the approaches currently in use.

The problems and challenges of the tools of the ORMF will be reflected upon later in this series. It is however fair to say that their design and implementation have contributed to a lack of Operational Risk understanding. There are many more challenges with the methods of the ORMF, including gaps or missing methods.

This article gives a view where Risk Management finds itself and lays a foundation for the future of Operational Risk Management. Clearly, innovation is required.

Covid-19 changed how the world operates and interacts – permanently. Organisations and individuals responded to the effects of the pandemic out of natural instinct; the consequences of not doing so would have been catastrophic. Organisations acted promptly and proactively to stem the negative effects of the various crises. At the heart of this instinct was the need to survive – a clue for the direction of Operational Risk.

We believe innovation is required to make markets – and the businesses within them -thrive. Get in touch at https://finmio.co/contact-us/